The Raphael case:

A 19th century copy in the Prado?

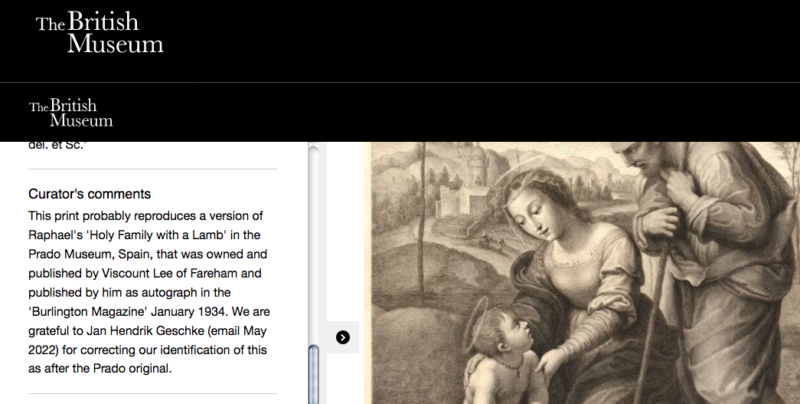

It is a holy cow, albeit with a lamb. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (or rather incorrectly so called Holy Family with the Lamb) is one of the great unsolved mysteries of western art history. Which version is Raphael’s original? Which one is a copy or even a fake? Generations of venerable art historians have fought desperately over this. As is so often the case, one long hard look can see the truth. Which made British Museum’s chief curator for prints, the most honourable Hugo Chapman, kindly correct this attribution of a Gregori engraving of the work made in ca. 1750 on the pages of the museum, even mentioning who came up with the accurate description. My sincerest thanks for that, much obliged! More revelations to follow in the very near future.

Seit bald 200 Jahren prügeln sich der Welt führende Kunsthistoriker, welche Fassung der Heiligen Familie mit dem Lamm (eigentlich eine Ruhe auf der Flucht nach Ägypten) nun die wahre, echte sei. Zu meiner großen Freude schloß sich der höchst ehrenwerte Hugo Chapman, seines Zeichens Chefkurator für Prints am British Museum, meiner Ansicht an und korrigierte die Zuschreibung eines Gregori-Stiches von ca. 1750, sogar unter Namensnennung des Korrektors, dafür meinen großen Dank! Mehr Erleuchtung zu diesem faszinierenden Fall, in dem schon viele ganz Große viele ganz kleine Details nicht gesehen haben, in Bälde. Stay tuned.

The Raphael case:

A 19th century copy in the Prado?

It is a holy cow, albeit with a lamb. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (or rather incorrectly so called Holy Family with the Lamb) is one of the great unsolved mysteries of western art history. Which version is Raphael’s original? Which one is a copy or even a fake? Generations of venerable art historians have fought desperately over this. As is so often the case, one long hard look can see the truth. Which made British Museum’s chief curator for prints, the most honourable Hugo Chapman, kindly correct this attribution of a Gregori engraving of the work made in ca. 1750 on the pages of the museum, even mentioning who came up with the accurate description. My sincerest thanks for that, much obliged! More revelations to follow in the very near future.

Seit bald 200 Jahren prügeln sich der Welt führende Kunsthistoriker, welche Fassung der Heiligen Familie mit dem Lamm (eigentlich eine Ruhe auf der Flucht nach Ägypten) nun die wahre, echte sei. Zu meiner großen Freude schloß sich der höchst ehrenwerte Hugo Chapman, seines Zeichens Chefkurator für Prints am British Museum, meiner Ansicht an und korrigierte die Zuschreibung eines Gregori-Stiches von ca. 1750, sogar unter Namensnennung des Korrektors, dafür meinen großen Dank! Mehr Erleuchtung zu diesem faszinierenden Fall, in dem schon viele ganz Große viele ganz kleine Details nicht gesehen haben, in Bälde. Stay tuned.

The Jan Beerstraten Case:

Picture estimated by auction house at 10k€ has a twin brother in the Rijksmuseum.

The exquisite „Dutch Ships in a Foreign Port“ (© Rijksmuseum) by Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraten, resting for eternity around the corner from this art detective’s Amsterdam field office in Westerkerk, has a twin brother. I discovered this when asked to verify the meagre estimate of ten thousand Euros by an auction house whose name will here be withheld, reserving themselves the right to buy it. Which turned out to be a marvelous idea, since a number for the value of the one in the Rijksmuseum would be more like 500k. Leaving my client ample money for cleaning (you couldn’t see anything due to 500 years of patina, identification wasn’t hindered much by that, though), since he of course most happily withdrew the picture.

Das entzückende „Dutch Ships in a Foreign Port“ (© Rijksmuseum) von Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraten, der bekanntlich direkt um die Ecke von meinem Amsterdamer Art Fraud Expert office in der Prinsengracht in der Westerkerk beerdigt liegt, hat ein Geschwisterchen. Dies fand ich heraus, als ein Klient mich bat, den etwas mageren Estimate von 10.000 € eines hier ungenannt bleibenden Auktionshauses zu verifizieren. Man behielt sich auch noch das Recht vor, zu diesem Preis selbst zu kaufen, eine erstklassige Idee, da der von mir nach Identifikation ermittelte Wert eher bei 500k€ liegt. Was meinem Klienten nach Rückzug des Lots durchaus Geldmittel für die Reinigung von 500 Jahren Patina läßt, die fast jedes Detail auf dem Bild überdeckten.

The Jan Beerstraten Case:

Picture estimated by auction house at 10k€ has a twin brother in the Rijksmuseum.

The exquisite „Dutch Ships in a Foreign Port“ (© Rijksmuseum) by Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraten, resting for eternity around the corner from this art detective’s Amsterdam field office in Westerkerk, has a twin brother. I discovered this when asked to verify the meagre estimate of ten thousand Euros by an auction house whose name will here be withheld, reserving themselves the right to buy it. Which turned out to be a marvelous idea, since a number for the value of the one in the Rijksmuseum would be more like 500k. Leaving my client ample money for cleaning (you couldn’t see anything due to 500 years of patina, identification wasn’t hindered much by that, though), since he of course most happily withdrew the picture.

Das entzückende „Dutch Ships in a Foreign Port“ (© Rijksmuseum) von Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraten, der bekanntlich direkt um die Ecke von meinem Amsterdamer Art Fraud Expert office in der Prinsengracht in der Westerkerk beerdigt liegt, hat ein Geschwisterchen. Dies fand ich heraus, als ein Klient mich bat, den etwas mageren Estimate von 10.000 € eines hier ungenannt bleibenden Auktionshauses zu verifizieren. Man behielt sich auch noch das Recht vor, zu diesem Preis selbst zu kaufen, eine erstklassige Idee, da der von mir nach Identifikation ermittelte Wert eher bei 500k€ liegt. Was meinem Klienten nach Rückzug des Lots durchaus Geldmittel für die Reinigung von 500 Jahren Patina läßt, die fast jedes Detail auf dem Bild überdeckten.